It was the advent of the Edinburgh Review in 1809, soon followed by Murray's own

Quarterly Review, of the commercial potential for journals of opinion, that provoked

Byron into the public sphere. He had already published some minor and largely forgettable lyrics, but it was a bad review of these that first ignited the volcano of his splenetic talent...it was in derision that Byron first found a public voice, and came into the view of

John Murray.

From 'English Bards and Scotch Reviewers'

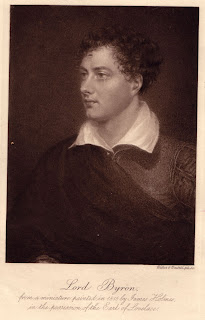

BYRON

Still must I hear? --- shall hoarse Fitzgerald bawl

His creaking couplets in a tavern hall,

And I not sing, lest, haply, Scotch reviews

Should dub me scribbler, and denounce my muse?

Prepare for rhyme --- I'll publish, right or wrong:

Fools are my theme, let satire be my song.

Laugh when I laugh, I seek no other fame;

The cry is up, and scribblers are my game.

I too can scrawl, and once upon a time

I pour'd along the town a flood of rhyme,

A schoolboy freak, unworthy praise or blame;

I printed --- older children do the same.

"T is pleasant, sure to see one's name in print;

A book's a book, although there's nothing in 't.

READER

Byron sets about the literary world with careless violence, poets and critics and publishers...

BYRON

And think'st thou, Scott ! by vain conceit perchance,

On public taste to foist thy stale romance,

Though Murray with his Miller may combine.

To yield thy muse just half-a-crown per line?

READER

I wonder whether Byron thought of HIMSELF as a poet at this point, thought of poetry as the arena where he would live his life. We must remember that "being a writer" was not then what it is now. It was an accomplishment of Ladies and gentlemen, perhaps...or it was a grubby little job of public entertainer. Poetry as existential vocation is an invention of the romantic age, and in temprement, at this point, Byron seems like a man out of his time...he belongs more to the world of Addison, Pope and Steele, than to that of Southey and Wordsworth...whose choice of vulgar subject matter is held up to withering aristocratic scorn.

BYRON

With eagle pinion soaring to the skies,

Behold the ballad-monger Southey rise !

Immortal hero ! all thy foes o'ercome,

For ever reign --- the rival of Tom Thumb !

Next comes the dull disciple of thy school,

That mild apostate from poetic rule,

The simple Wordsworth, framer of a lay

As soft as evening in his favorite May,

when he tells the tale of Betty Foy,

The idiot mother of "an idiot boy;"

A moon-struck, silly lad, who lost his way,

And like his bard, confounded night with day;

So close on each pathetic part he dwells,

And each adventure so sublimely tells,

That all who view the "idiot in his glory"

Conceive the bard the hero of the story.

READER

I must confess that as a student, when I first encountered this Byron, Byron the classical reactionary, I

was little inclined to read further. I loved Wordsworth...I loved his conscience...his seriousness...I was as serious as a deacon myself...which I suppose makes the point, that Byron the poet could not exist for me, until my existence was open to him...

For one thing, these days, as a public writer myself, I can enjoy his advice to critics...

BYRON

Fear not to lie, 't will seem a sharper hit;

Shrink not from blasphemy, 't will pass for wit;

Care not for feeling --- pass your proper jest,

And stand a critic, hated yet caresss'd.

READER

But if Byron had stopped here, as was entirely possible before his discovery of himself as a poet on his European journey soon after, then he would be remembered as an critic, albeit an unusually witty and careless one.

BYRON

Sonnets on sonnets crowd, and ode on ode;

And tales of terror jostle on the road;

What varied wonders tempt us as they pass;

The cow-pox, tractors, galvanism, and gas,

In turns appear, to make the vulgar stare,

Till the swoln bubble bursts --- and all is air !

These are the themes that claim our plaudits now;

These are the bards to whom the muse must bow;

While Milton, Dryden, Pope, alike forgot,

Resign their hallow'd bays to Walter Scott.

READER

But it was Byron's having a pop at the Edinburgh review, that Whiggish success story to which Murray put up a Tory , rival and competitor, that first brought his Lordship to Murray's attention, perhaps prompting him to read the manuscript that Byron produced when he returned from his travels, and which transformed both their lives. Partly for local reference, here's a sample...

BYRON

Dark roll'd the sympathetic waves of Forth,

Low groan'd the startled whirlwinds of the north;

Strew'd were the streets around with milk-white reams,

Flow'd all the Cannongate with inky streams;

Arthur's steep summit nodded to its base,

The surly Tolbooth scarcely kept her place.

For long as Albion's heedless sons submit,

Or Scottish taste decides on English wit,

So long shall last thine unmolested reign

Nor any dare to take thy name in vain.

READER

I think Murray probably enjoyed that. But no more thought than Byron did that they were shortly to create something quite unprecedented between them...

was little inclined to read further. I loved Wordsworth...I loved his conscience...his seriousness...I was as serious as a deacon myself...which I suppose makes the point, that Byron the poet could not exist for me, until my existence was open to him...

was little inclined to read further. I loved Wordsworth...I loved his conscience...his seriousness...I was as serious as a deacon myself...which I suppose makes the point, that Byron the poet could not exist for me, until my existence was open to him...